Event-driven architectures with Kafka have become a standard way of building modern microservices. At first, everything works smoothly - services communicate via events, state is rebuilt from event streams, and the system scales well. But as your data grows, you face an inevitable challenge: what happens when you need to access historical events that are no longer in Kafka?

1. The Problem: Finite Retention & The Need for Backfills

In a perfect world, we would keep every event log in Kafka forever. In the real world, however, storing an ever-growing history on high-performance broker disks is prohibitively expensive.

This leads to the inevitable compromise: data retention policies. We keep a few weeks or months of events in Kafka for real-time processing and offload the rest to cheaper, long-term cold storage like Amazon S3. This process becomes part of a general Data Lake sink strategy.

This works well until a scenario arises that demands access to the full historical record, for example:

- Bootstrapping a New Service: A new microservice needs to build its own materialized view of the world by processing the entire history of events.

- Recovering from a Bug: A subtle bug is discovered in a service, and you need to rebuild its state from a point in time months ago.

- Enriching Data for New Features: A new feature requires historical context, forcing a re-process of old events.

The core problem is the same: how do we gracefully rehydrate our services with data that now lives in cold storage?

2. The Backfill Blueprint: A Two-Phase Process

Backfill can be broken down into two distinct phases:

- Phase 1: Sourcing the Data: First, we must establish a reliable way to get the stream of historical events from cold storage.

- Phase 2: Consuming the Data: Second, we need a robust strategy for our service to process this historical stream safely, without disrupting live traffic.

3. Phase 1: Sourcing Historical Data

There are three primary architectural patterns for sourcing historical data that is no longer in Kafka.

Pattern 1: Kafka Tiered Storage

The most elegant solution is one that eliminates the need for a separate ETL process: using a Kafka distribution that supports Tiered Storage. This feature allows Kafka to automatically move older event segments to object storage like S3, while the topic’s log remains logically intact and infinitely queryable. The data is physically in two places, but Kafka presents it as a single, seamless stream.

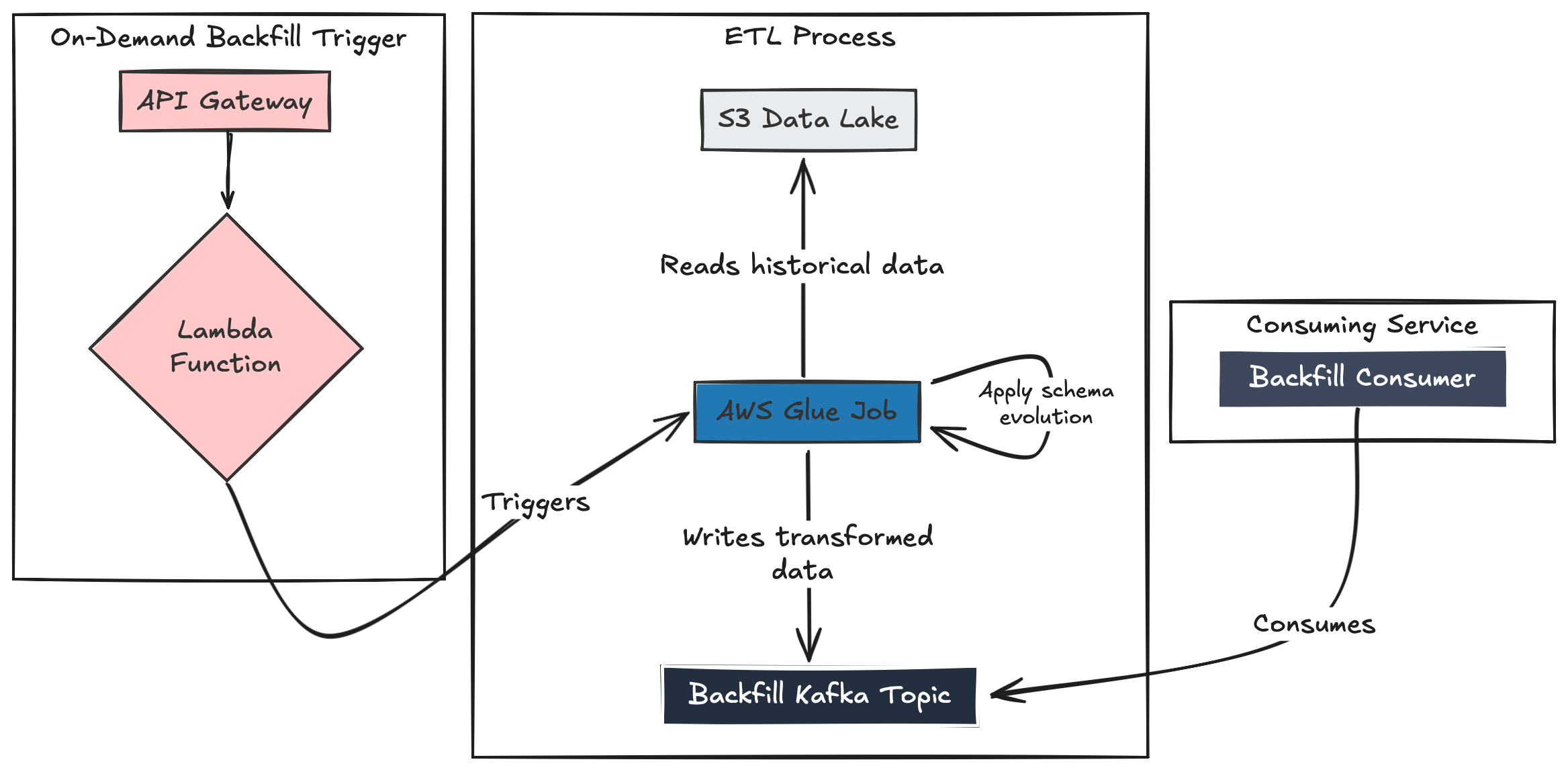

Pattern 2: ETL Bridge

If you don’t have Tiered Storage, you need a safe, reliable bridge between your S3 data lake and Kafka. The core of this pattern is a generic, on-demand ETL job (AWS Glue or Spark is a perfect fit) that reads from S3 and produces it onto a dedicated, temporary backfill topic (e.g., events.backfill). This isolates the historical load from the live stream, preventing disruption to real-time consumers.

Handling Schema Evolution: Using a schema registry, the ETL job can perform a “schema-on-read” transformation. It reads multiple historical Avro schema versions from S3, evolves each record to the latest schema version, and writes the clean data to the backfill topic. This means the service consumer only needs to be aware of the latest schema.

Pattern 3: Pull-Based Backfill (Bypassing Kafka)

In some scenarios, re-populating a Kafka topic is unnecessary overhead. Instead, the service needing the data can fetch it directly from its long-term storage location.

This pattern simplifies the data platform but shifts complexity to the consuming service. It must now contain logic to read from two different sources, merge the streams, and handle potential event ordering conflicts. Unless you can afford to isolate the backfill and run it before the service goes live.

Alternative A: Direct Lake Query

If you have query engines like Trino set up, your service can bypass Kafka for historical data. It can implement a job that directly queries S3 via Trino, fetching and processing data in controlled chunks.

Alternative B: Service-to-Service Backfill

When historical data still resides in the source service’s live database. The source service provides a paginated API, allowing the consuming service to pull the history in manageable batches.

While often faster to set up, this approach puts a direct and heavy read load on a live production service. This can degrade the source service’s performance, so mitigation is essential;

- Control the Load: Throttling, rate-limiting.

- Schedule Wisely: Run the backfill during off-peak hours if possible.

- Isolate the Impact: Scale resources accordingly, use a database read replica if possible.

- Monitor

4. Phase 2: Consuming Historical Data

Getting the data is only half the challenge. The consuming service must be architected to handle rehydration safely.

Idempotent Processing is Non-Negotiable

When a service re-processes historical events, it will inevitably encounter data it has already seen. The consumer logic must be idempotent, meaning that processing the same event multiple times produces the same result as processing it once. This is the foundational prerequisite for any safe backfill strategy.

Choose Your Consumption Strategy

A. The Simple Replay

For many use cases, like enriching data for an analytics model or rebuilding a non-critical cache, the strategy is simple. A dedicated consumer reads from the backfill source until it is empty. The job is complete when all historical data has been processed. This approach is perfect for stateless tasks or systems that can afford a brief maintenance window to switch over.

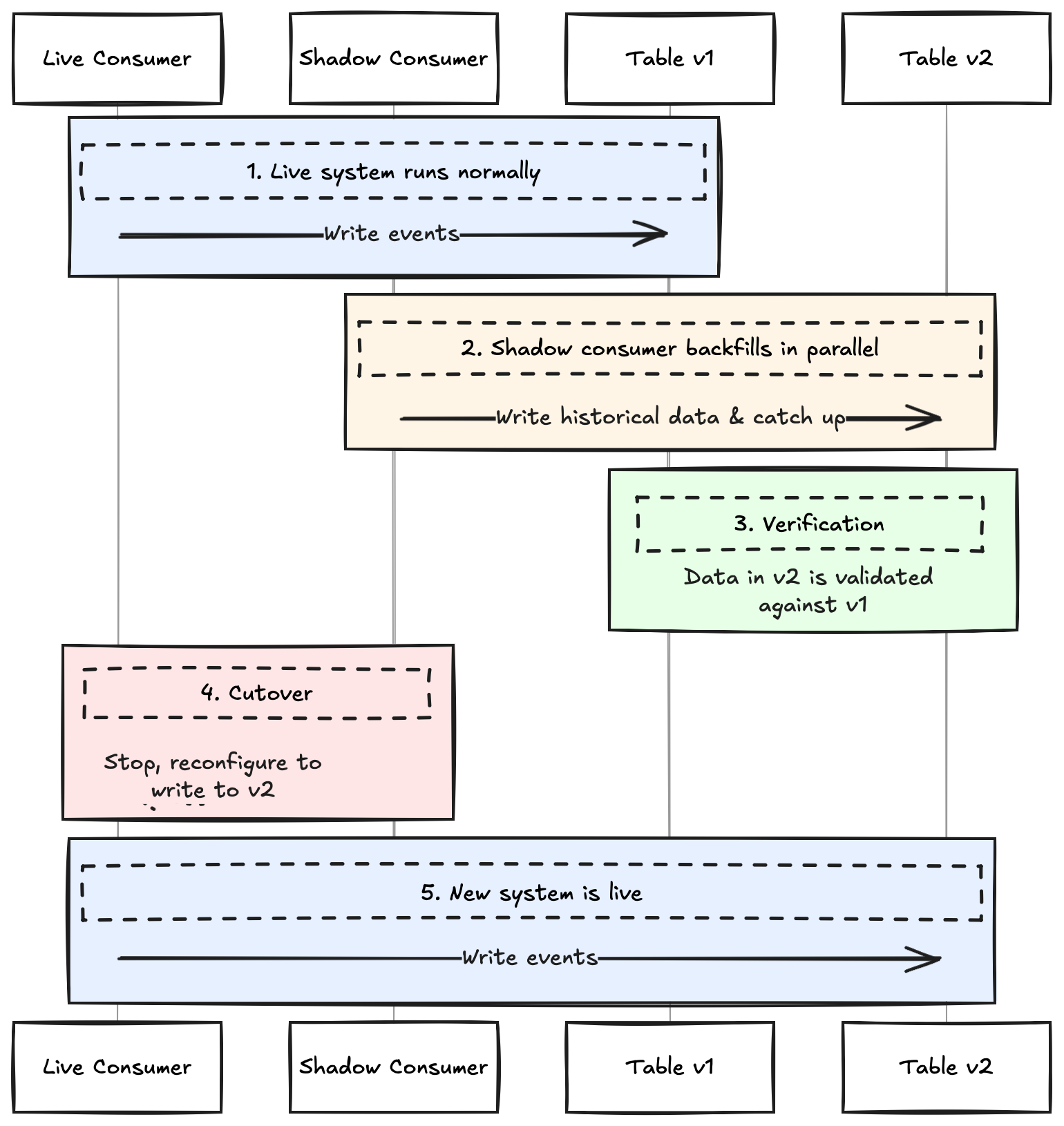

B. The Zero-Downtime Migration (The Shadow Pattern)

For critical, stateful services that cannot have downtime, a more sophisticated strategy is required. This strategy rebuilds a system using the Shadow Migration pattern. It’s a specific implementation of Parallel Change, sometimes called the Shadow Table Strategy, where a “shadow” process runs alongside the live service before a final, coordinated cutover.

Run in Parallel: A “shadow” consumer reads the entire event history, writing to the new table (

v2). Simultaneously, the existing “live” consumer continues its normal operation, writing only to the old table (v1).Catch Up: The shadow consumer runs until it has processed all historical data and is keeping up with the live topic in near real-time.

Verify Consistency: Run validation jobs to ensure data in

v2is consistent withv1. This critical go/no-go step confirms that the migration is safe to complete.Execute the Cutover: The final switch can be handled in two ways, depending on the system’s downtime tolerance.

A. Hard Cutover (Simpler/Faster)

For systems that can tolerate a brief service pause, you can skip dual writes. This involves stopping the live consumer, reconfiguring it to write only to

v2, and restarting it at the same time you repoint the application’s reads tov2. This must be a single, atomic action.B. Dual-Write Cutover (Safer/Zero-Downtime)

For critical systems, reconfigure the live consumer to write to both

v1andv2. This keeps both tables perfectly in sync, creating a safe, indefinite window to verifyv2under a live load before repointing the application reads at your leisure.Decommission: After a period of monitoring the new table, the process is complete. If you used the dual-write method, reconfigure the consumer one last time to write only to

v2. Finally, remove the oldv1table and any legacy code.

To prevent any missed events during the handoff, the live consumer should rewind its offset to slightly before where the shadow consumer finished. This creates a small, intentional overlap of events. For this reason, idempotent processing is absolutely essential, as it allows the system to handle these duplicates gracefully without corrupting data.

5. Optimizing the Backfill with Snapshots

Replaying every event from the beginning of time can be slow. For many use cases, you can accelerate the process by using a snapshot—a precomputed, materialized state of your data.

- State Snapshots: A periodically generated full snapshot of an entity’s state. Rehydration then involves loading this snapshot and replaying only the events from Kafka that have occurred since the snapshot was created.

- Kafka-Native Snapshots (Log Compaction): For services that only need the current state of an entity, Kafka’s log compaction provides a powerful, built-in solution. A compacted topic retains at least the last known value for each message key. Reading this topic from the beginning provides a consumer with a full, live snapshot of the current state.

In short: use State Snapshots when you need a point-in-time view plus the full event history that followed; use Log Compaction when you only need the latest value for every entity, not their history.

6. Execution

A successful backfill requires more than a solid architectural blueprint; it demands disciplined execution. Some operational best practices to mitigate risk and ensure a predictable outcome;

- Monitoring and Observability: A backfill should never be a “black box.” Track key metrics like consumer lag, processing throughput, and resource utilization in real-time. This is the only way to detect bottlenecks or failures before they cascade.

- Resilience and Failure Handling: The process must be resumable. Large backfills can take hours or days, and failures are inevitable. By tracking progress, it can resume where it left off, saving significant time and resources.

- Cost Awareness: A large-scale data replay can incur significant costs from compute resources (ETL jobs, consumer pods) and cloud data egress. Model these costs beforehand to avoid budget surprises.

- Incremental Testing: Naturally don’t run a full-scale backfill for the first time in production. Validate the entire process with a small, representative slice of data in a staging environment to catch logical errors and performance issues early.

Ultimately, a historical data backfill is a planned, two-phase process for sourcing and consuming historical data. It can be done in a controlled and repeatable manner When you combine the right architectural patterns with operational best practices.